A Word by Way of Introduction

The work of the painter and graphic artist Pavel Mutinský from Plzeň has traversed and continues to traverse several main thematic circles.

The first significant thematic circle presented here in the Goethe Gallery is the city and civilization theme. Structural abstraction, material experiments, gradual transformations, and pushing boundaries to the point of optical reality, the search for a visual equivalent of the external and internal form of the subject became his starting point for depicting the city as a model. The city through which the painter passes as an observer "from the outside" and a participant "from the inside". Remarkably, in his paintings, the boundaries between the "outside" and the "inside" vanish, remaining only to say through his works: The city is my fate and yours. Run from it, return to it, love it or hate it, its sediment of dust from its streets and the scent of memories lived in it will always remain within you. He never claimed that the city is and will be the cornerstone of his lasting interest, but still... Robust, rugged, and poetic city, city symbol, in the light of neon lights, city at twilight, city at night, the city between day and night, in its compositional diversity, it has been receiving and continues to bring people to their knees with its everyday poetry and "factory of neuroses".

Pavel Mutinský is a painter in graphics and a graphic artist in painting. The development of the formal expression of his paintings was undoubtedly influenced by his material alchemy, which is to say, experiments in the field of informel that he developed and perfected with his own obsession. He learned to work with screens, structures, the abbreviation of modern graphic signs, fragments of typeface. He can use these elements in such a way that, based on verified facts, his experimentation leads to an understanding of the optical expression of the era in which we live, defining it in a unique way. Thanks to his graphic and design training, he can afford to enter his paintings from constructive, rational, intuitive positions and thus prepare a "foundation" for the resonance of his sensuality and emotions. This provides significant support for successfully clarifying the dominant content perspective.

Another significant circle of the author's work is landscape painting. The exhibition represents it primarily through paintings created based on study and work trips he undertook throughout the entire decade of the 1990s to Northern and Western Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. For him, these trips meant not only extraordinary experiences but also a challenge to visually record the atmosphere of these diverse locations. He perceived an architecture so different from Europe's that it would satisfy many artists to "fill" their canvases with it, different customs, culture, and history. But he also sensed an intoxicating explosion of scents, tastes, and sounds. The mentality of the local residents, their life rhythms echoing among the weathered walls of minarets and exotic structures, also became imprinted on his canvases. The mystery, diversity, contrasts, the gentle trembling of the hot air that warms the human foot pressed into the ground, the walls of houses, the domes of marabouts, but also the fates of the people living there—all of this he "brought back." Exploring the extraordinary atmosphere of these places became a successful creative period for the painter, leaving behind unforgettable experiences and images richly filled with emotions. As a result of this enchantment, the return to European presence in painting was even more challenging.

The author's third significant circle of work is figurative painting, primarily represented in the exhibition by female nudes. In the seventeenth century, the philosopher Baruch Spinoza said that an emotion ceases to be an emotion as soon as we create a clear and distinct idea of it. I would dare say that the opposite is true for Mutinský's nudes. Despite creating a fairly clear idea of the beautiful female body in his compositions, the emotions, excitement, desire that we read from his paintings are very, very contagious! Let the puritans return to their world full of emptiness.

The large-format canvas that "opens" this exhibition, and from its title alone, anyone can understand that it's a paraphrase of the theme of Édouard Manet, belongs to a cycle of variations on well-known classical themes. In the past, painters like Diego Velázquez or Leonardo da Vinci also caught the painter's attention. Paraphrase means a clear and succinct expression of a certain state, feeling, or impression, using one's own means. In his paraphrases, the painter never stops admiring the original works, resonating with their composition, and often intentionally pushing their content. Through his variations, he tries to convey what time "added" to these works by leaping centuries from their creation. The original source gives him space to express how the past transposed into the present doesn't lose its influence on our perception of these artistic treasures.

In 2019, he painted the canvas "City Between Day and Night," where we can sense the city awakening at dawn to a new day. From the very beginning, the painter continues to move his creations between night and day. This allows him to experience not only the weight of darkness but also the hope of dawn. Interestingly, even in the current special times, touches of beauty and sensitive harmony still dominate in his paintings. Let's wish him that. Let's wish it to him and to ourselves! Only then will he be able to convey touches of beauty and sensitive harmony to us, the receptive ones, standing before his paintings.

Pavel Hejduk, July 2022

Interview Before the Exhibition

In August 2015, you had a major retrospective exhibition in Prague, a cross-section of your forty-year painting and graphic work. For the Municipal Museum in Mariánské Lázně, you've prepared a second exhibition on a similar principle, also retrospective. How do these two exhibitions differ from each other?

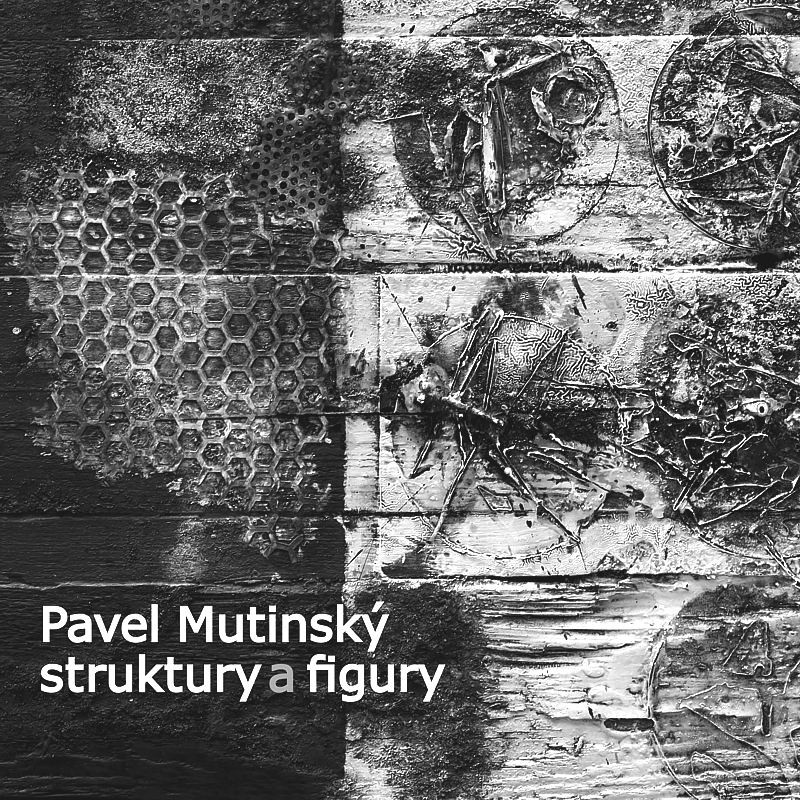

Certainly by scope, concept, and selection of works. Quite significantly. The Prague exhibition was conceived as a single extensive collection in one large space. It was possible to visually grasp the entire exposition from one point. The current exhibition is more intimate, with a selected collection of works organized according to development, respecting motifs and genres, into three loosely interconnected sections. The common denominator of the first section could be structural abstraction and material experiments, which I began creating already in the initial phase, even before the mid-1970s, and continued to create until the end of the 1980s. But the beginnings were a bit more complicated.

Influenced by my first teacher, the painter and graphic artist Vladimír Havlic, I went through a phase of smooth tempera painting. Over time, however, I began to feel a certain routine, little creative invention, even a stereotype. Feelings of dissatisfaction increasingly led me to combine techniques and experiment with various materials, which became more and more of an adventure for me. I created fictional anatomical panels, laboratories with specimens and hints of the animal world, organic tissues, insects, amphibians, which today we might call biomorphic compositions. Under my hands, compositions with elements of surrealistic-informel aesthetics were born, although back then we used the term "poetically tuned" instead of "surrealistic," as surrealism wasn't in vogue during the normalization period. Informed, and perhaps inspired by the post-surrealist circle of the Prague art school, I created works on the border between painting, relief, collage, and assemblage. I tried experimenting with dispersion, combining oil painting with coatings, mixing my own putties, layering varnishes, often preparing the image surface with a surgical scalpel, and sometimes flames helped with destruction. I created compositions that were quite distant from Havlic's concept of painting. A contemporary theorist would probably say: He was entranced by informel procedures. However, in the 1970s, we didn't know the term "informel"; we used phrases like "structural graphics, structural painting, structural or material abstraction."

Going from smooth tempera painting to structures is quite a leap. How did Vladimír Havlic react when he saw your shift?

He, as a graduate of Professor František Muzika's studio at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, naturally preferred precise drawing and painting built on honest drawing and well-defined contours. It wasn't hard to guess that he wouldn't be overly enthusiastic about my experiments, so I didn't unnecessarily provoke him with that. For a while, I pursued both approaches simultaneously—officially one, the other in my drawer. I now believe he knew about this and secretly observed which approach would prevail in me. I think he wished for both himself and me not to produce another Havlic, for me not to become his epigone.

After some time, I gifted him one of my structural abstractions, a symmetrical A4-sized decal. He had it hanging in his studio in Lobzy among his older works, so I assume that if he could look at it every day, he might have appreciated it.

You've mentioned Vladimír Havlic, but in professional biographies, you usually mention three professors who influenced your development, especially during your student years. If I'm not mistaken, a significant influence on your artistic development was Docent Milan Hes, is that correct?

Yes, that's right. In the mid-1970s, I saw two of Hes's paintings for the first time in the apartment of our mutual acquaintance. At that time, I had no idea that fate would later bring us together in the roles of teacher and student, and later as colleagues and close friends. Shortly after I started at the faculty, in October 1978, we met in person, and during this first meeting, he invited me to his studio. I admit that when I walked to his studio, I was nervous. He was a complex personality, a somewhat inaccessible sovereign. Later, I realized that his somewhat grand gestures were just an external expression of defense, masking a vulnerable sensitive soul.

As we talked in the studio, my nervousness gradually subsided. We spoke hastily, often changed topics, interrupted each other as if we needed to quickly convey everything each of us had experienced until the moment of the meeting. We discussed art, especially the 1960s. At that time, my mind was filled with Boudník, Janošek, Istler, Medek, Koblasa, and I know that he undoubtedly went through the same at some point, so he probably knew exactly what was happening in my student mind. I brought some of my works to show him, the "drawer ones" that I considered dark underground, as I sensed a kindred conspiratorial soul in him. His laconic response only reinforced my suspicion: Yeah, it's nice..., but don't bring it to school.

Hes taught painting in the style of suggestion. To imply, to suggest, not to reveal everything right away. He held onto this approach in artistic and personal expression. Just as he painted, that's how he was. Artistic expression reveals many aspects of our inner selves.

I owe him much. He indicated the path out of the somewhat bland cycle of smooth tempera painting. Among other things, in 1986, he wrote a great introduction to my solo exhibition catalog, in which he published the then-current idea of my civilian expression building on the legacy of Group 42 and even personally inaugurated the exhibition. He helped me with the exhibition installation several times, having a peculiar ability to appear unexpectedly but precisely when needed. It's a pity that he couldn't come to terms with my decision, to opt for a "regular" career in independent work instead of an artistic-pedagogical one by his side. It was the time of my rapid creative surge, the 1980s. Society wasn't characterized by complete ideological tolerance, which forced many artists, including me, into a certain duality, a kind of creative schizophrenia. One part of my work could be and was publicly presented, while the other part, due to acts of self-censorship in exhibitions, except for exceptions, remained hidden. Over time, I "healed" from this creative schizophrenia, but the healing process was very slow. I believe I reached complete convergence, even merging, of those two aspects after twenty-five years, mainly through three consecutive paintings: Avenue H.B., Transfer into an Unknown Megapolis, and City Between Day and Night.

What was the cause of, let's say, a certain "delay" and perhaps insight?

After November '89, the 90s came full of upheavals. Commercial galleries sprang up like mushrooms after rain, and I realized that I was succumbing to the external pressure from gallery owners. Slowly but systematically, they were turning me, an independent freelance painter, into a dependent "image producer." Instinctively, I felt the need for a break. So, for a while, my free creative work deliberately took a back seat. I established a graphic studio, which led me to focus more on applied art and the organizational activities necessary for business.

This was followed by about a decade of work and study trips, primarily to North and West Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. The environment of the Orient completely absorbed me and provided many ideas, challenges, and inspiration. I started painting the atmosphere of destinations with different climates, cultures, and histories. Thanks to the sun and the mentality of the local inhabitants, my palette had brighter tones, and new paintings gained a more vivid and colorful palette, at least for a while... during a time of euphoria.

A convergence of many previously unimaginable events led me to touch the ground again and return to seeing the world through the eyes of a Central European expressing concerns about the future direction of the world and human civilization. I put away the rose-colored glasses.

So, is the common denominator of the second part of the exhibition the Orient? Or perhaps the perception of the world without rose-colored glasses?

The second part is thematically very broad. It includes landscape painting in general, including subjects from travels, as well as urban and civilizational themes - naturally without rose-colored glasses.

And the third part? If the subtitle of this exhibition is "From Informel to Figurative Painting," and since we haven't talked about figures yet, logically it suggests that it consists of figurative painting.

Yes. The exhibition is dominated by a large figurative composition representing my variations on well-known themes by famous authors. In this case, it's Manet's picnic. The third part, or rather thematic segment, consists of figurative painting, primarily female nude. However, my figurative painting cannot be understood as a temporally limited phase, and certainly not as a closed thematic unit. Figurative motifs have accompanied me since the mid-1980s, and I started focusing more intensively on the theme of the female nude in the early 1990s, and I still enjoy it today. The mentioned subtitle of the exhibition is not meant to express a chronological axis or sequence; rather, it indicates the breadth of thematic diversity.

During your studies, you also met with Professor Josef Šteffel. What was he like?

He was a person with whom everyone interacted with great care. A national artist, a significant figure, a high-ranking official, chairman of the regional organization of the Union of Czech Fine Artists. No one had the slightest interest in antagonizing him.

He taught painterly composition - image construction. I shortened his method to "cubization." The principle was to transform a realistic (descriptive) subject into complete formal disintegration. Through several stages, there was a gradual degradation, breaking down into reduced geometric forms, overlapping or intertwining them. In the final phase, a composition resembling abstraction emerged. Some intermediate phases formally resembled synthetic cubism, hence my abbreviation.

Did you enjoy it? Did you feel that this method was useful for your painting style?

Absolutely, it was an interesting and creative activity, very beneficial from an educational perspective, especially for understanding modern art. Just as Hes, in a sense, opened my eyes with his guidance, Šteffel also pushed me further. He provided me with instructions on how to organize the surface of the painting, especially how to express space through the arrangement of planes without converging perspective lines.

How did you get along with each other?

Very well. But I remember the feeling of uncertainty during the first meeting with him. I would almost consider it certain that if someone preferred socialist realism during normalization and strictly adhered to it, it would be him - the union chairman. And there he was in front of my painting Twilight Over the City. In front of a painting with enamel structures and informal forms that could no longer be realism, let alone socialist realism, was distant from. Moreover, this happened at school, in the office of the head of the department! I expected that I would be in trouble and that Hes would be as well, due to me, as a student, acting ideologically inappropriately. However, something quite peculiar happened. He stood in front of that painting, examined its details up close, stood there silently, and really unusually long. So, I got the impression and was afraid that he was searching for words, thinking about his speech to express disappointment, disapproval, negative evaluation, or reprimand. But to my surprise, he said this: So, you're technically equipped... what year are you in? I'm looking forward to having seminars together.

Naturally, our relationship was entirely different from the relationship with Milan Hes. No jokes, no informality. He was serious, thorough, and serious.

At the beginning of the fifth year, I experienced another big surprise when, as the only student from my year, he submitted a proposal to the dean for my individual study. The justification read: Based on previous studies and achieved academic results, I propose... I had no idea that something like this even existed. Thanks to him, I didn't have to attend daily lectures and seminars for two whole semesters. I didn't have to deal with things I already knew. I had plenty of time for self-study and my own creations. I painted, and I brought finished paintings for credit. Somewhat naively, I imagined that this is how my future life in a freelance profession might look.

Another big surprise, orchestrated by him, awaited me shortly after my studies. While still serving in compulsory military service, I was invited to submit a portfolio of paintings to Gallery U Řečických in Prague for assessment by a committee as part of the acceptance of new artists into the registry of the Czech Fund of Fine Arts. I received my first card, which was of great value to me, from his hands. It may sound unbelievable, but this is what a teacher-student relationship can look like, even when they don't share the same worldview, they can still respect and value each other.

The author was interviewed on July 3, 2022, by Pavel Hejduk.